Glaucoma

Highlights

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness. While glaucoma can develop in anyone, people over age 60, who have a family history of glaucoma, or who are African-American are at especially high risk. Certain types of medical conditions, such as diabetes or extreme near-sightedness, can also increase the risk for glaucoma.

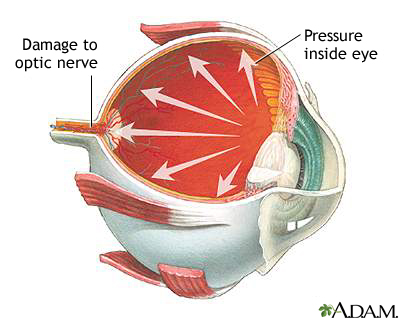

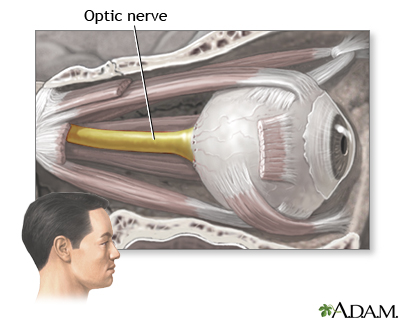

Glaucoma is a term used to describe several types of eye conditions that affect the optic nerve. In many cases, damage to the optic nerve is caused by increased pressure in the eye, also known as intraocular pressure (IOP).

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

- Primary open-angle glaucoma is the most common type of glaucoma.

- In primary open-angle glaucoma, poorly functioning drainage channels prevent fluid from being released from the eye at a normal rate. This in turn causes a rise in intraocular pressure.

- People with primary open-angle glaucoma usually experience few or no symptoms until the later stages of the disease, when vision loss becomes apparent.

Treatment

There is no cure for glaucoma, but treatment can help reduce intraocular pressure and prevent optic nerve damage and blindness. Glaucoma is usually treated with medications, although surgery may also be recommended for some patients.

Medication

Most glaucoma medications are usually given in the form of eye drops. Make sure your doctor or ophthalmologist explains to you the correct way to administer these drops.

A number of different medications are used to treat glaucoma. They include:

- Prostaglandins, such as latanoprost (Xalatan) and tafluprost (Zioptan)

- Beta-blockers, such as timolol (Timoptic, Betimol, generic)

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, such as dorzolamide (Trusopt, generic) and brinzolamide (Azopt)

- Alpha agonists, such as apraclonidine (Iopidine, generic) and brimondidine (Alphagen, generic)

Introduction

Glaucoma is a term used to describe several types of eye conditions that result in optic nerve damage.

In many cases, damage to the optic nerve is caused by abnormally increased pressure in the eye, a condition known as high intraocular pressure (IOP) or ocular hypertension.

High intraocular pressure results from the buildup of aqueous humor, the clear fluid that circulates within and flows out of the front (anterior) chamber of the eye. Aqueous humor helps nourish the area around the colored iris and behind the cornea. To maintain normal eye pressure, the same amount of aqueous humor that is produced within the eye drains out from the eye.

Aqueous humor flows out through an open angle between the iris and cornea (the drainage angle.) It then passes through a sponge-like network of cells called the trabecular meshwork and exits the eye, eventually flowing into the bloodstream.

Excessive eye pressure occurs when problems arise with the drainage angle so that aqueous humor is trapped and builds up within the eye. Over time, high IOP can cause damage to the fibers of the optic nerve, resulting in the condition known as glaucoma. However, glaucoma can sometimes also develop in people who have normal eye pressure. Poor blood flow to the optic nerve may be another possible factor in causing optic nerve damage.

.

There are several types of glaucoma.

Open-Angle Glaucoma

Open-angle glaucoma (also called primary or chronic open-angle glaucoma) is the most common form of the disorder.

Open-angle glaucoma is essentially a plumbing problem. The drainage angle remains open, but tiny drainage channels in the trabecular meshwork pathway become clogged, causing the aqueous humor to flow out of the eye too slowly. The fluid continues to be produced but does not drain out efficiently. The result is increased ocular pressure. Open-angle glaucoma tends to start in one eye but eventually involves both eyes.

Closed-Angle Glaucoma

Closed-angle glaucoma (also called angle-closure or narrow-angle glaucoma) is less common than open-angle glaucoma in the U.S., but it constitutes about half of the world's glaucoma cases because of its higher prevalence among Asians.

Closed-angle glaucoma occurs when the iris is pushed against the lens closing off and blocking the drainage angle. The aqueous humor cannot drain out and eye pressure increases. The rise in pressure usually occurs very suddenly (a condition called acute closed-angle glaucoma). Less commonly, eye pressure can gradually increase over time (chronic closed-angle glaucoma).

Normal-Tension Glaucoma

Eye pressure (intraocular pressure) is considered high when it is over 21 mm Hg (millimeters of mercury). Most people with glaucoma have a high IOP. However, some people develop optic nerve damage and vision loss even when their IOP is in a normal range (10 – 21 mm Hg). This is called normal-tension, or low-tension, glaucoma.

Congenital Glaucoma

Congenital glaucoma, in which the eye's drainage canals fail to develop correctly, is present from birth. It is very rare, occurring in about 1 in 10,000 newborns. This is often an inherited condition and can usually be corrected with microsurgery.

Secondary Glaucoma

Secondary glaucoma is glaucoma caused by another disease or condition. Both open-angle glaucoma and closed-angle glaucoma can be secondary conditions.

Secondary glaucoma can result from medications, eye injuries or trauma, medical conditions such as diabetes, or inherited conditions. Two types of secondary glaucoma that have a genetic component are:

- Pseudoexfoliation (PEX) syndrome is marked by dandruff-like flakes that accumulate on the surface of the eye’s lens. The material can clog the drainage angle of the eye and lead to build-up of intraocular pressure. PEX has a strong genetic component but other factors (possibly sunlight, an autoimmune response, or a slow virus) may be needed to trigger the disease.

- Pigmentary Glaucoma starts with a condition called pigment dispersion syndrome, an inherited condition in which granules of pigment (the substance that colors the iris) flake off into the intraocular fluid. These fragments clog the trabecular meshwork and can increase intraocular pressure.

Causes

Causes of Open-Angle Glaucoma

Doctors don’t know exactly what causes the the inefficient drainage process associated with primary open-angle glaucoma. The trapped aqueous humor builds up slowly over time, causing increased intraocular pressure and, eventually, damage to the optic nerve. But other factors may also produce optic nerve damage.

Causes of Closed-Angle Glaucoma

People with acute closed-angle glaucoma often have a structural defect that produces a narrow angle between the iris and cornea where the aqueous humor circulates. This structural defect makes them more susceptible to developing closed-angle glaucoma.

In acute closed-angle glaucoma, conditions that dilate (widen) the pupils may cause this shallow angle to suddenly close. Such conditions may include certain drugs (antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, some asthma and anti-seizure medications), darkness or dim light, and emotional stress.

Causes of Normal-Tension Glaucoma

Research suggests that glaucoma in people with normal eye pressure may be due in part to poor blood flow to the optic nerve.

Causes of Secondary Glaucoma

When glaucoma is caused by other diseases or conditions, it is known as secondary glaucoma.

Medical Conditions. A number of diseases can contribute to the development of secondary open-angle or closed-angle glaucoma:

- Diseases that affect blood flow to the optic nerve (such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and migraine)

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland)

- Sleep apnea

- Physical injury to the eye or previous eye surgery

- Extreme nearsightedness (myopia)

- Other disorders, including leukemia, sickle cell anemia, and some forms of arthritis

Medications. Corticosteroids, commonly called steroids, are a type of drug that has multiple effects on the trabecular meshwork. Steroids come in eyedrop, pill, and inhaled forms. The risks for glaucoma are greatest with corticosteroid eyedrops. However, all types of corticosteroids can increase glaucoma risk when they are taken in high doses or for prolonged periods of time.

Risk Factors

About 4 million Americans have open-angle glaucoma, the most common type of glaucoma (accounting for about 90% of all glaucoma cases). Half of these people are unaware they have glaucoma because the condition causes no pain or visual changes in its early stages.

Risk factors for glaucoma include:

Increased Intraocular Pressure (IOP)

Elevated intraocular pressure is associated with increased risk of optic nerve damage and glaucoma.

Age

The risk of developing glaucoma increases with age. Everyone over age 60 is at risk of developing glaucoma. People in certain racial or ethnic groups are at higher risk of developing glaucoma at younger ages.

Race and Ethnicity

Compared to Caucasians, African-Americans are 5 times more likely to develop glaucoma, and 4 times more likely to become blind because of it. African-Americans are also much more likely to develop glaucoma at younger ages. For African-Americans, the risk of developing glaucoma begins at age 40. Hispanic Americans are also at increased risk, especially after age 60.

People of Asian descent have a slightly greater risk than other racial groups of developing closed-angle glaucoma. Normal-tension glaucoma is very common in people of Japanese ancestry.

Family History

Glaucoma tends to run in families. This is especially true for primary open-angle glaucoma. People with family histories of glaucoma are also more likely to already have some vision loss when they are first diagnosed with glaucoma.

Medical Conditions

Diabetes and hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) are the main medical conditions associated with increased glaucoma risk. High blood pressure and migraine headaches are also risk factors. Certain eye conditions, including nearsightedness (myopia), and previous eye surgery also boost risk.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Open-Angle Glaucoma

Open-angle glaucoma is a chronic condition that develops slowly over many years. In its earliest stages, it produces no pain, visual changes, or other symptoms. As the condition progresses and the optic nerve becomes damaged, the following symptoms appear in one or both eyes:

- Peripheral vision (vision from the side of the eyes) gradually decreases. Patients develop “tunnel vision,” the ability to see only straight ahead.

- Eventually, straight-ahead vision decreases.

If left untreated, blindness results.

Symptoms of Closed-Angle Glaucoma

In acute closed-angle glaucoma, the pressure inside the eye increases quickly, and the symptoms are dramatic. Intense pain in the eyebrow area and blurred vision develop usually in one eye, and the patient often feels like the eye will burst (although it won't). The eye usually reddens. A person may see rainbow-like halos around lights. Sometimes nausea and vomiting occur. These symptoms may occur on and off and not appear as a full attack. In either case, they indicate a medical emergency. In chronic closed-angle glaucoma, the process is gradual and painless.

Symptoms of Congenital Glaucoma

Although congenital glaucoma is usually present at birth, symptoms generally don’t develop in the infant for a few months. If parents notice that an infant’s eyes are enlarging, becoming cloudy, often watering, or tending to close in the presence of light, they should have an ophthalmologist examine the child’s eyes. Port-wine stains on an infant’s face could indicate Sturge-Weber syndrome, a disorder that occasionally causes glaucoma.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment of glaucoma and prevention of blindness. Because chronic glaucoma has no warning symptoms, half of patients are unaware they have the condition.

A diagnosis of glaucoma does not depend solely on the presence of increased pressure within the eye. Optic nerve damage or a strong indication of damage must also be present.

Recommendations for Glaucoma Screening

There has been debate about the relative benefits and risks of routine glaucoma screening in adults. Glaucoma screening can help identify signs of increased intraocular pressure (IOP) and the early stages of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). However, treatment of IOP and early POAG can potentially result in harmful effects, such as eye irritation and increased risk for cataracts. Because of this uncertainty, the United States Preventive Services Task Force has not found sufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for glaucoma in adults.

In contrast, the American Academy of Ophthalmology strongly supports glaucoma screening, with the following specific recommendations:

- Everyone over age 65 and African-Americans over 40 years old should have periodic eye exams, including tests for glaucoma, every other year.

- African-Americans ages 20 - 39 should have eye examinations every 3 - 5 years.

- Other people at higher risk (people with diabetes, history of eye injuries, a family history of glaucoma, or those taking corticosteroid medications) should have eye examinations every year after age 35.

- People with known glaucoma should have frequent examinations to check peripheral vision and to be sure treatment is maintaining a safe eye pressure. After such examinations, the ophthalmologist will assess current treatment and make necessary adjustments.

Tonometry and Pressure Tests

Doctors determine IOP using a painless procedure called tonometry, which measures the force necessary to make an indentation in the eye. They may use a tonometer (small smooth instrument). There are several methods, and the doctor may apply anesthetic eye drops to first numb the eye:

- The applanation (Goldman) method, uses a blue-light filter and slit-lamp, which is moved forward toward the patient's face.

- Electronic indentation tonometry uses an electronic pen with a digital read-out.

- The noncontact approach does not use a tonometer. It applies a puff of air to measure the force needed to indent the eye.

- In the Schiotz method, the doctor presses very lightly against the eye with the tonometer. IOP is measured by the weight needed to flatten the cornea. This method is not considered as accurate as the others.

In general, normal IOP is usually maintained at measurements of 10 - 21 mmHg. Intraocular pressure over 21 mmHg indicates a potential problem. The test is not completely accurate, however. Only about 10% of people with IOP levels of 21 - 30 mmHg will actually develop glaucoma and optic nerve damage. On the other hand, many people with glaucoma have normal pressure, at least for part of the time.

Measurement of Cornea Thickness (Pachymetry)

Cornea thickness is an important indicator of disease progression in patients with elevated IOP. The doctor first applies numbing drops to the eye and then uses an ultrasonic wave instrument to measure cornea thickness.

Tests for Optic Nerve Damage

To check for damage in the optic nerve, the doctor first uses eye drops to dilate (widen) the pupils and then examines the eyes with a magnifying lens instrument such as an ophthalmoscope, which has a light on one end.

Damaged nerve fibers may be indicated by:

- An asymmetrical or elongated cupped optic nerve. (The cup of the optic disc is the center portion, which enlarges as nerve damage progresses.)

- The optic nerve color may be pale or an unhealthy pink.

Visual Field Tests

The doctor will conduct tests of the visual fields (the areas that the patient can see). In most people with glaucoma, the first areas to become noticeably impaired are the peripheral visual fields (areas of sight that are not directly in front of a person but around the edges, or periphery).

Tests for Closed-Angle Glaucoma

Using an instrument called a gonioscope, ophthalmologists can inspect the front of the eyes and assess the drainage angle between the cornea and the iris and the channels in the trabecular meshwork. This test can help differentiate between closed- and open-angle glaucoma.

Treatment

Glaucoma cannot be cured, but treatment may help delay disease progression. Most treatments for glaucoma aim to reduce ocular pressure and its fluctuations. Early treatment with medications, surgery, or both can nearly always maintain safe pressure of the aqueous humor, thus preventing optic nerve damage and blindness.

Decision to Start Treatment

Many people have high IOP but no sign of nerve damage. Over the course of 20 years, only 10 - 30% of these people will actually develop glaucoma. Nevertheless, once glaucoma has destroyed optic nerve fibers, no treatment can reverse the damage.

However, not all people with high eye pressure develop optic nerve damage and serious vision problems. Nor does treatment prevent progression in some patients. Medications used for glaucoma also can carry side effects and risks.

Some doctors recommend delaying treatment for people with borderline or early signs of glaucoma until they begin to show risk factors for progressive disease and vision loss (thinner corneas, larger cup to optic disc ratio, older age, and rising pressure).

Considerations for Drug Treatments

There are many different drugs for treating glaucoma. The drugs reduce pressure in the eye but all have a number of side effects that affect other parts of the body. Occasionally, some side effects can be severe.

Many of the drugs used for glaucoma can interact with common medications for other conditions. And, many patients require two or more drugs. If your doctor prescribes more than one medication, be sure you understand when you should take each drug and how long you should wait between applying each drop. Ask your doctor to write down a schedule for you. Let your doctor know if you experience any side effects. To prevent optic nerve damage, it is very important to take your medication on a regular basis and not skip doses.

Most glaucoma medications are given as eye drops. These drugs decrease eye pressure by reducing the production of aqueous humor or by helping the fluid drain more efficiently:

- Prostaglandin-like drugs are generally the first-line treatment for glaucoma. They include latanoprost (Xalantan), bimatroprost (Lumigan), travaprost (Travatan), and tafluprost (Zioptan).

- Beta-blockers such as timolol (Timoptic, generic) and other brands are a second choice.

- Alpha agonists, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), and miotics are other drug therapies.

- Some drugs are available are available as combination eye drops. For example, Cosopt combines the beta blocker timolol and CAI dorzolamide. Combigan combines timolol and the alpha agonist brimonidine.

Treating Pregnant Patients. Considerations for a pregnant woman with glaucoma can be complicated. All of the drugs used for glaucoma are absorbed by the body, cross the placenta, and are excreted in breast milk. Many have effects that can interfere with or adversely affect pregnancy.

Women should discuss going off medication, particularly during the first trimester, and be monitored during that time for increasing eye pressure. IOP tends to drop during pregnancy, although usually not to a significant degree. In addition, changes in IOP and visual loss vary greatly. Some women have no IOP change or visual loss during pregnancy, while others may experience an increase in IOP or worsening of visual loss. Your ophthalmologist must carefully consider your individual case and talk with you about the risks and benefits of continuing glaucoma medication during pregnancy. If women need to take medications, they should try to take the lowest effective dose possible.

Considerations for Surgery

The goal of standard glaucoma surgery is to reduce pressure in the eye by increasing the outflow of the aqueous fluid. Two methods are commonly used:

- Filtration surgery (trabeculectomy). This uses standard surgical instruments to open a passage in the eye for draining fluid.

- Laser trabeculoplasty. This procedure uses a laser to burn tiny holes in the drainage area.

In general, surgery is used for patients who have not been helped by medications. However, in some cases doctors may recommend surgery before or in place of drug treatment. Surgery does not cure glaucoma, and over half of patients will need medication or a repeat surgical procedure within 2 - 5 years.

Medications

Nearly all glaucoma medications are prescribed to reduce eye pressure. They generally work by reducing the production of aqueous humor and increasing fluid outflow (drainage). In most cases, these drugs are taken as eye drops. If drops alone do not work, your doctor may also prescribe a medication to be taken by mouth.

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins are hormone-like substances that help widen blood vessels. Drugs that mimic natural prostaglandins increase the drainage of aqueous humor to help reduce intraocular pressure. Prostaglandin-like drugs are the first-line treatment for glaucoma.

Latanoprost (Xalatan, generic) is the standard brand. Latanoprost was the first prostaglandin to be approved as first-line treatment for elevated eye pressure. Three newer prostaglandins are travoprost (Travatan), bimatoprost (Lumigan),and tafluprost (Zioptan). These drugs are used to reduce eye pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma and high ocular pressure.

Side effects include itching, redness, and burning during administration. Muscle and joint pain may also occur. All of these drugs may permanently change eye color from blue or green to brown.

Beta-blockers

Topical beta-blockers lower the pressure inside the eye by inhibiting the production of aqueous humor.

Timolol (Timoptic, Betimol, generic) is the standard brand. Other examples of beta-blockers used for glaucoma treatment are levobunolol (Betagan, generic), carteolol (Ocupress, generic), metipranolol (OptiPranolol, generic), and betaxolol (Betoptic, generic).

After a beta-blocker is administered, only a tiny amount of the drug is absorbed by the cornea. Most of it enters in the bloodstream. These drugs, therefore, can cause side effects in parts of the body other than the eyes ("systemic" side effects). Beta-blockers may:

- Cause reduced sexual drive, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and breathing difficulties.

- Lower heart rate and reduce blood pressure.

- Worsen severe asthma or other lung diseases.

- Cause a sudden rise in eye pressure, particularly if a patient has switched to a beta-blocker from another type of glaucoma medication. It is important that IOP be checked shortly after the other drug has been withdrawn.

- When beta-blockers are used to treat one eye, the other (contralateral) eye also experiences a lesser, but still significant reduction in IOP.

Topical beta-blockers can interact with oral medications, such as other beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, or the antiarrhythmic drug quinidine. People with diabetes who take insulin or hypoglycemic medications should be aware that beta-blocker side effects may mask the symptoms of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) are used for glaucoma when other drugs do not work. They may be combined with other medications.

In addition to reducing aqueous humor production, CAIs may improve blood flow in the retina and optic nerve (beta-blockers do not). Improving blood flow can keep the disease from getting worse.

CAIs are available in the following forms:

- Eye-drop CAIs include dorzolamide (Trusopt, generic) and brinzolamide (Azopt). Side effects may include stinging in the eye, watery or dry eyes, or bitter taste. Brinzolamide is a newer medication that may cause less stinging than dorzolamide.

- Oral forms include acetazolamide (Diamox, generic) and methazolamide (Neptazane, generic). Although pill forms are more effective than eye drops, they have significantly more side effects and are rarely used for long-term treatment. Unpleasant side effects include frequent urination, stomach problems, and tingling in fingers and toes. People who are allergic to sulfa drugs or who have a history of kidney stones should not use these drugs. CAIs can also produce a toxic reaction when taken with large doses of aspirin.

Alpha Agonists

Alpha agonists, also called adrenergic agonists, reduce the production of aqueous humor and increase drainage.

Apraclonidine (Iopidine, generic) and brimonidine (Alphagan, generic) are the alpha agonists used for glaucoma treatment. They are generally used before glaucoma surgery, but may be useful as primary therapy when used in combination with beta-blockers or other standard drugs.

The most common side effects are dry mouth and altered taste. Alpha agonists may also trigger an allergic reaction that causes red and itching eyes and lids. Brimonidine causes less of an allergic response than apraclonidine. Unlike apraclonidine, however, it can cause lethargy and mild low blood pressure.

Miotics

Miotics, also called cholinergic agonists, narrow the iris muscles and constrict the pupil. This action pulls the iris away from the trabecular meshwork and allows the aqueous humor to flow out through the drainage channels, reducing the pressure inside the front of the eye.

Pilocarpine (Isoptocarpine, other brands, generic) was the most widely used anti-glaucoma drug before timolol was introduced. It is the preferred miotic. However, it has to be taken several times a day and many people have difficulty complying with this regimen. Carbachol (Isopto) is another miotic.

Epinephrine and its derivatives are the older therapies. Epinephrine is now rarely prescribed because of side effects. Dipivefrin (Propine), a newer form of epinephrine, is effective in low doses and causes few systemic side effects.

Side Effects. Side effects may include:

- Teary eyes, brow-aches, eye pain, and allergic reactions.

- A miotic narrows the pupil and so can cause nearsightedness. Vision can become dim and it may be difficult to see in darkened rooms or at night, making driving difficult.

- Miotics increase the risk of cataract development and are therefore used mostly in patients in whom cataracts have already been removed. Retinal detachment is an uncommon but dangerous side effect in susceptible individuals.

Managing Drug Regimens

Many patients skip doses of their glaucoma medications, sometimes because of side effects and sometimes because of confusing or time-consuming regimens. Skipping even a few doses can greatly increase the risk of visual loss. It is essential that you inform your doctor if you are not regularly taking your medication. Otherwise, your doctor may increase the dosage, thereby causing unwelcome side effects.

Patients who do not regularly take their glaucoma medication are at high risk for blindness. If you have problems taking your medications or sticking to the dosing regimen, talk with your doctor.

Hints for Managing a Regimen.

- Pharmaceutical manufacturers use colored tops, yellow for timolol, for example, and green for pilocarpine, to help prevent mix-ups. Creating a chart scheduling each drug by color can be helpful.

- Small electronic timers are available that will signal times for taking the medications. The timing of these combinations is important.

- Some patients may be candidates for single medications that combine two drugs, such as Cosopt, which contains both dorzolamide and timolol. This medication requires only one drop twice per day. Patients who need additional glaucoma drugs, however, will need to take these two drugs separately.

- When using any drug for a long period of time, side effects are a potential problem. If they become severe, ask your doctor about reducing the dosage or trying other drugs.

Administering Eye Drops. A common reason that glaucoma medicine does not work is that patients do not take it correctly. Patients should ask the ophthalmologist to watch while they place the drops in their own eyes to make sure they are doing it correctly. The following are some recommended steps:

- If you use both ointments and eye drops, take the eye drops first.

- Wash your hands before applying eye drops.

- Hold the bottle upside down.

- Tilt your head back and, with one hand, pull the lower eyelid down to form a pocket.

- With your other hand, hold the bottle as close as possible to your eye. Don’t let the bottle directly touch your eye or eyelid.

- After you have placed the drop, close your eye or press your index finger against the corner of the eye near your nose. Gently move the lower lid upward until the eye is closed. Keep your eye closed for at least 1 minute. This prevents the drop from draining out.

- Wait at least 5 minutes before applying another drop or a different medication

Drug Therapy for Acute Closed-Angle Glaucoma

Acute closed-angle glaucoma is an emergency situation. Doctors may administer a combination of two or more medications to reduce eye pressure quickly before it can damage the optic nerve and cause visual loss. Apraclonidine (Iopidine, generic) is a powerful drug used before and after laser surgery to prevent an increase in fluid pressure and is more effective than other medications. In addition to standard drugs, doctors may also administer glycerin by mouth or mannitol or acetazolamide intravenously. Surgery is almost always performed once the pressure is reduced.

Surgery

If medications do not control eye pressure, or if they create severe side effects, surgery may be necessary. The standard procedures are usually one of the following:

- Laser surgery (trabeculoplasty). This procedure partially opens the drainage area. It does not reduce pressure as much as filtering surgery (trabeculectomy) but it has fewer adverse effects.

- Filtration surgery (trabeculectomy). This conventional surgery procedure opens the full thickness of the drainage area.

Laser Surgery (Trabeculoplasty)

Laser trabeculoplasty is used to treat open-angle glaucoma. It involves the following steps:

- The procedure uses a laser to burn 80 - 100 tiny holes in the drainage area. The two main types of surgery are argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) and selective laser trabeculloplasty (SLT).

- A tiny scar forms, which increases fluid outflow.

- The procedure is performed on an outpatient basis, takes 15 minutes, causes almost no discomfort, and has very few complications.

Laser surgery is not a cure. Although it reduces intraocular pressure, patients still need to take medications every day. Within 2 - 5 years eye pressure increases and most patients require either additional surgery or new medications.

Filtration Surgery (Trabeculectomy)

Filtration surgery has been used for more than 100 years with only minor modifications. It uses conventional surgical techniques known as full-thickness filtering surgery or guarded filtering surgery (trabeculectomy).

- The surgeon creates a sclerostomy, a passage in the sclera (the white part of the eye) for draining excess eye fluid.

- A flap is created that allows fluid to escape without deflating the eyeball.

- The surgeon may also remove a tiny piece of the iris (called an iridectomy) so that fluid can flow backward into the eye.

- A small bubble called a bleb nearly always forms over the opening, which is a sign that fluid is draining out. Although surgeons aim for a thick bleb, which poses less risk than a thin one for later leakage, the ideal operation would have no bleb at all.

- The procedure is usually performed on an outpatient basis but some patients may need to stay overnight in the hospital.

For many patients, trabulectomy eliminates the need for medications. In some patients, eye pressure eventually increases again and patients may need to go back on medication or undergo a second trabeculectomy.

A newer instrument called a trabectome allows for a less invasive type of trabulectomy surgery. The trabectome procedure uses an electrosurgical pulse to remove a small section of the trabecular meshwork.

Side Effects. Many of the serious side effects or complications that occur with filtration surgery involve blebs (blister-like bumps).

- Bleb Leaks and Infections. Blebs, particularly thin ones, commonly leak. Leakage can occur early on or sometimes as late as months or years after surgery. Untreated, leaks can be serious and even cause blindness. Surgical repair is the most effective way of managing leaking blebs, although drug therapies, pressure patching, and other nonsurgical techniques may be tried first. Due to the dangers of leaking blebs, doctors recommend lifelong monitoring after surgery.

- Scarring. In some cases, scars form around the incision, closing up the drainage channels and causing pressure to rebuild. Scarring is a particular problem in young patients, African-Americans, and patients who have taken multiple drugs, have had an inflammatory disease, or have had cataract surgery. Releasing the surgical stitches used in the procedure may help prevent scarring and pressure build-up. A second procedure called bleb needling can sometimes open up the scarred area and restore drainage. With this technique, the tip of a very fine hypodermic needle is used to carefully cut loose the particles closing off the drainage area. Drugs may also be used to prevent scarring.

- Cataracts. The procedure is highly associated with the development of cataracts over time. Because cataracts are associated with glaucoma anyway, it is not entirely clear whether the cataracts are caused by the surgery or would develop in any case.

Drainage Implants (Tube Shunts)

Drainage implants, also known as tube shunts or aqueous shunts, may be used to drain fluid if patients have not been helped by laser or filtration surgery. They are also used to treat children with glaucoma.

The procedure is performed in an operating room using a local anesthetic. The procedure involves:

- An implant, most commonly a 1/2 inch silicone tube, is inserted into the eye's front (anterior) chamber.

- The tube drains the fluid onto a tiny plate that is sewn to the side of the eye.

- Fluid collects on the plate and then is absorbed by the tissues in the eye.

- The patient wears an eye patch and shield until the first post-operative visit. Healing time takes about 6 - 8 weeks.

Complications are uncommon but may include very low eye pressure (hypotony), drooping eyelid, double vision, and retinal detachment. Occasionally the tube falls out and needs to be replaced.

Surgery for Acute Closed-Angle Glaucoma

Acute closed-angle glaucoma is an emergency situation that requires immediate medical attention. Doctors will first try to quickly reduce eye pressure using medications, and then perform surgery.

Laser iridotomy is the standard procedure. It uses a laser to make a small hole in the iris to allow the aqueous humor to flow out more freely. In some cases, conventional surgery, called peripheral iridectomy, may be performed. It involves surgically removing a small piece of the iris.

Laser iridotomy almost never requires hospitalization, and postsurgical treatment includes only aspirin and eye drops. It has almost completely replaced conventional surgery, which requires anesthesia and hospitalization.

Vision will be blurred, and recovery can take 4 - 8 weeks. Following surgery, patients can usually safely use previously restricted anticholinergic medications, such as antihistamines and certain antidepressants. In many cases, doctors recommend performing an iridotomy on the other eye at a later date.

Treatment for Patients with both Glaucoma and Cataracts

Cataracts and Glaucoma. For patients with both glaucoma and cataracts, doctors recommend:

- In patients with cataracts and poorly controlled glaucoma, a two-step procedure for both eye conditions is needed. Typically the patient will first have a trabeculectomy for glaucoma, followed by cataract surgery such as phacoemulsification (lens removal through ultrasound). Fluid leakage and the presence of blood in the back chamber of the eye are potential complications of this combined procedure.

- Phacoemulsification is sometimes combined with viscocanalostomy in a procedure called phacoviscocanalostomy.

- In patients who have cataracts plus either closed-angle glaucoma or open-angle glaucoma that is stabilized with medication, the cataract may be able to be extracted and medication continued for the glaucoma.

Some evidence indicates that the combined approach generally offers better control of eye pressure for patients with both cataracts and glaucoma. However, it is still unclear which specific type of surgical procedure works best.

Lifestyle Changes

Exercise

Some evidence suggests that regular exercise may modestly reduce eye pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Exercise has no effect on closed-angle glaucoma.

Exercise can be dangerous for patients who have pigmentary glaucoma. Vigorous high-impact exercise causes pigment to be released from the iris, which increases eye pressure.

Glaucoma patients should avoid yoga and other exercises that involve head-down or inverted positions. Talk with your doctor about an appropriate exercise program.

Diet

Antioxidants in Foods and Supplements. Diet most likely plays very little role in glaucoma. There has been no definitive evidence for an association between important nutrients associated with protection against other eye disorders, including vitamins C, E, A, and carotenoids.

Caffeine. Some studies have shown that large amounts of caffeine drunk in a short period of time can elevate eye pressure for up to 3 hours.

Fluids. Drinking large amounts (a quart or more) of any liquid within a short time, about 30 minutes, appears to increase pressure. Patients with glaucoma should have plenty of fluids, but they should drink them in small amounts over throughout the day.

Sunglasses

Glaucoma can cause the eyes to be very sensitive to light and glare. Medications can worsen this problem. Sunglasses solve this problem and are important for prevention of cataracts. Protective sunglasses do not have to be expensive. But it is important to select sunglasses whose product labels state they block at least 99 percent of UVB rays and 95 percent of UVA rays.

Polarized and mirror-coated lenses do not offer any protection against UV radiation. It is not clear if blue light-blocking lenses, which are usually amber in color, provide UV protection.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

A number of herbal and nontraditional remedies have been advertised as glaucoma remedies. A few studies have reported that the herbal remedy ginkgo biloba may have properties that offer benefits to patients with glaucoma, including increasing blood flow in the eye without altering overall blood pressure, heart rate, or intraocular pressure. More research is needed. There is no evidence that bilberry, another popular herbal remedy for eye disorders, is effective in preventing or treating glaucoma.

Marijuana can lower ocular pressure, but only for a few hours, and it is no more effective than prescription medications. Due to its lack of long-term effectiveness, and mood-altering side effects, marijuana is not recommended for glaucoma treatment.

Resources

- www.glaucoma.org -- Glaucoma Research Foundation

- www.nei.nih.gov -- National Eye Institute

- www.glaucomafoundation.org -- The Glaucoma Foundation

- www.aao.org -- American Academy of Ophthalmology

- www.americanglaucomasociety.net -- American Glaucoma Society

- www.lighthouse.org -- Lighthouse International

References

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary Angle Closure: Preferred Practice Pattern. Updated October 2010.

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Preferred Practice Pattern. Updated October 2010.

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Suspect: Preferred Practice Pattern. Updated October 2010.

Aptel F, Cucherat M, Denis P. Efficacy and tolerability of prostaglandin analogs: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Glaucoma. 2008 Dec;17(8):667-73.

Cheng JW, Cai JP, Li Y, Wei RL. A meta-analysis of topical prostaglandin analogs in the treatment of chronic angle-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2009 Dec;18(9):652-7.

Cheng JW, Wei RL, Cai JP, Li Y. Efficacy and tolerability of nonpenetrating filtering surgery with and without implant in treatment of open angle glaucoma: a quantitative evaluation of the evidence. J Glaucoma. 2009 Mar;18(3):233-7.

Gedde SJ, Heuer DK, Parrish RK 2nd; Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study Group. Review of results from the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar;21(2):123-8..

Hernández R, Rabindranath K, Fraser C, Vale L, Blanco AA, Burr JM; OAG Screening Project Group. Screening for open angle glaucoma: systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies. J Glaucoma. 2008 Apr-May;17(3):159-68.

Higginbotham EJ. Managing glaucoma during pregnancy. JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296(10):1284-5.

Jampel H. American glaucoma society position statement: marijuana and the treatment of glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2010 Feb;19(2):75-6.

Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WL. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 12;360(11):1113-24.

Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Dong L, Yang Z; EMGT Group. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007 Nov;114(11):1965-72. Epub 2007 Jul 12.

Pasquale LR, Kang JH. Lifestyle, nutrition, and glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2009 Aug;18(6):423-8.

Quigley HA. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2011 Apr 16;377(9774):1367-77. Epub 2011 Mar 30.

Rivera JL, Bell NP, Feldman RM. Risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma progression: what we know and what we need to know. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar;19(2):102-6.

Rolim de Moura C, Paranhos A Jr, Wormald R. Laser trabeculoplasty for open angle glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD003919.

Rosenberg EA, Sperazza LC. The visually impaired patient. Am Fam Physician. 2008 May 15;77(10):1431-6.

Stewart WC, Konstas AG, Nelson LA, Kruft B. Meta-analysis of 24-hour intraocular pressure studies evaluating the efficacy of glaucoma medicines. Ophthalmology. 2008 Jul;115(7):1117-1122.e1. Epub 2008 Feb 20.

Vizzeri G, Weinreb RN. Cataract surgery and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan;21(1):20-4.

|

Review Date:

9/10/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |